Go MacBook Pro? (Part 1) — The Semantic Shift

Apple has done it again. The Apple rumour mill was a buzz with snippets of what an Intel Mac might look like but no one guessed that Apple would roll out a system that would outperform the current Apple PowerPC G4 line by as much as 4 times!

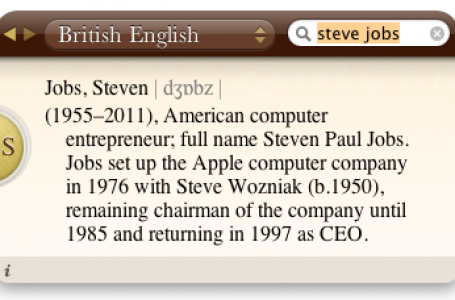

Following Apple CEO, Steve Job’s, keynote speech at MacWorld 2006, there is anxiousness among those who have just purchased 15″ PowerBook G4’s in the last week and hesitation in the rest who are looking to purchase their next Apple 15″ portable. Should we go Intel-based MacBook Pro or invest in a steadfast and matured PowerPC-based PowerBook G4?

This series of articles, attempts to unravel the factors to be considered and details that need putting under the microscope.

What has happened?

From 1994 to 2005 Apple used PowerPC CPUs in their line of computer hardware systems. The PowerPC CPU is the result of the Apple-IBM-Motorola (AIM) alliance that was originally founded to challenge the then dominant, Wintel computing platform, by producing a new computer design and a next generation operating system.

In 2003, after disappointing performance increases from Motorola, Apple turned to IBM to churn out its PowerPC G5 chips and in 2005 decided to take things one step further by getting onboard with Intel to further Apple’s thirst for performance increase in its hardware architecture.

Enter the dawn of the Intel-based era beginning with the MacBook Pro… In his MacWorld 2006 keynote speech, Apple CEO, Steve Jobs, has committed to migrating the entire Apple hardware line to Intel by the end of 2006. For now, only time can tell the realisation of this ambition.

Rosetta and Universal Applications.

Is there a difference?

The PowerPC chips are Reduced Instruction Set Computers (RISC) whilst Intel x86 chips are Complicated Instruction Set Computers (CISC). Both RISC and CISC processors inherently handle data and instructions differently and as such applications and programs need to be designed and compiled differently for each platform.

Before the introduction of Intel x86 processors into the Apple product line, this fundamental difference distinguished Macs from Windows PCs and, simplistically, explains why Mac applications could not run natively on Windows PCs and vice-versa.

What follows is a series of simplified illustrations which attempt to display what happens when applications are launched on a Mac system running Mac OS X currently and the impact the introduction of Intel x86 architecture has in store.

The Mac system is divided into layers where the Applications sit atop the Mac OS X operating system which in turn sit atop the Mac hardware. Here’s how it works. The Application layer talks to the Mac OS X operating system layer which in turn communicates with your Mac hardware and carries out the tasks as instructed. Once done, the Mac hardware, hands the results back up the chain and the loop continues until the task has been carried out.

Computers at the very base level handles data in binaries, which in lay man terms, is a series of one’s (1) and noughts (0). To keep things simple, lets just say a RISC processor communicates using RISC binaries whilst CISC processors use CISC binaries.

Diagram 1.0

RISC Binaries In PowerPC Macs

In a typical PowerPC-based Mac, applications are compiled in RISC binaries which communicate seemlessly with the Mac hardware through the Mac OS X operating system (Diagram 1.0).

Diagram 1.1, Mac OS X – Rosetta (Intel x86) Architecture

RISC Binaries In Intel Macs With Rosetta

Owing to the hurried schedule to roll out Intel-based Macs, Rosetta was introduced as an interim, transition measure to ease current PowerPC Mac users into the new Intel Mac world. Providing support for current PowerPC-based applications.

In the latest Intel-based Macs, Rosetta functions as an emulator that interprets RISC binaries into CISC binaries and vice-versa, sitting between the Mac OS X operating system and the Intel Mac hardware (Diagram 1.1). Because Rosetta sits between the Mac OS X operating system and the Mac hardware, its operation appears seemless to the user.

Owing to its function as an emulator, the process consumes resources with the consequence of rosetta-dependant applications taking a performance hit. Added to that there are limits to what Rosetta can translate which accounts for applications which cannot run atop Rosetta. Rosetta is the brainchild of a silicon valley startup, Transitive and at press time, its unclear whether the same technology can be used in reverse — to enable Intel x86 applications to run on PowerPC Macs.

Diagram 1.2, Mac OS X – Universal Binaries (PowerPC) Architecture

Diagram 1.3, Universal Binaries (Intel x86) Architecture

Universal Applications On PowerPC And Intel Macs

The other solution to this PowerPC and Intel Mac conundrum, is Universal binaries. In simple terms, Universal binaries include both PowerPC and x86 versions of a compiled application. The operating system detects a universal binary from its header, executing the appropriate section depending on the architecture in use.

In PowerPC Macs, the Mac OS X operating system detects the RISC binary from its header, uses it and dispenses with the CISC binaries (Diagram1.2).

The inverse occurs in Intel Macs, where CISC binaries are applied and RISC binaries dispensed (Diagram 1.3). Universal binaries are usually substantially larger than single-platform binaries, because two copies of the compiled code must be stored. They do not require extra working memory, however, because only one of those two copies is loaded into RAM for execution. This allows the application to run at full speed on either architecture, with no appreciable performance impact.

Summary

With the entry of Intel Macs, we are once again witnessing a system migration by Apple Computer Inc. Previously, a similar migration occured in May 2002 where Apple CEO, Steve Jobs, at Apple’s Worldwide Developers Conference in San Jose, California, delivered a mock funeral for Mac OS 9 during his keynote address, dressed in black and accompanied by a coffin. The purpose of the theatrics was to announce that Apple had stopped all development of OS 9. Mac OS 9.2.2, introduced in late 2001, was the final version of Mac OS 9.

To smooth the transition from OS 9 to Mac OS X, OS 9 Classic was introduced; which functioned as a compatibility layer that runs a complete Mac OS 9 installation within OS X for applications and hardware that require OS 9.

This time Rosetta takes precedence over OS 9 Classic and serves to mitigate the hardships of purchasing an Intel Mac before Apple manages to port Mac OS X and its applications over, to run natively on the Intel x86 platform. Although, not explicitly mentioned, this new development signals final curtains on OS 9 and its legacy.

The developer documentation for the Rosetta PowerPC emulation layer, which is designed to allow PowerPC Mac applications to run on the Intel processor, explicitly states that applications written for Mac OS 8 or 9 will not run on Intel x86-based Macs.

As great as Rosetta is to keep PowerPC Mac users happy with their new Intel Macs, its limitations show. The hardest hit are users of Apple’s Pro Applications, who have to pay a fee to get their Pro apps up to speed. Depending on the particular app in question. For now, its more of a wait and see stance here at Mac Riot since we’re more in the habit of acquiring tried and tested hardware, as opposed to being the early adopters who usually have to wade through the marshes before their out of the swamp.

Its still early days and this appears to only be, Stage One. Involving a hardware migration from PowerPC to Intel x86. Stage Two will open, when Apple transitions its operating system and associated applications to run natively on the Intel x86 platform to take full advantage of its speed and processing power. Finally, it may be a premature guess but, Stage Three. The shift of Apple from a consumer oriented IT company, to include a corporate front once the Mac install-base achieves critical mass, so that Steve can realise a market that has managed to elude him thus far.

Apple has traditionally ‘protected’ its operating system by means of encoding its BootROM with code, that a Mac operating system will seek during the startup process of a computer before its allowed to boot. It is believed, that it was with minor tweaks to the BootROM in 2003, that Apple ceased the ability of OS 9 to boot natively on Apple hardware.

Operating on a PowerPC platform also added an extra line of ‘defence’ but now with Mac OS X running, albeit with the assistance of Rosetta, on Intel x86 processors; the question that lies close to the heart of diehard Mac fans all over is whether, Apple plans to port Mac OS X completely, to run natively on Intel x86 processors. And in so doing, whether this will open pandora’s box to allowing Mac OS X to one day appear on traditional Windows rigs?

Whatever the case, judging by Apple’s previous migration from OS 9 to Mac OS X, it might be some time before a complete migration of the current Mac install-base transpires. OS 9 to Mac OS X took a little over 3 years and lasted till Mac OS X 10.2. Its a good guess that this next phase will consume a similar amount of time.

Until then, its still a viable option to purchase a PowerPC-based Mac but from historical reference, with financial gain being the biggest market driver, we will most likely witness a slowing in software development for PowerPC-based Macs in time. Which will most likely be the final push for PowerPC-based Mac users to make the switch to Intel Macs.

Next up, in Part 2 of our Intel Mac overview, we will attempt to compare PowerPC Mac hardware versus Intel Mac, with our focus on the 15″ PowerBook G4 versus the much awaited MacBook Pro. Stay tuned…